- Home

- Jerome Tuccille

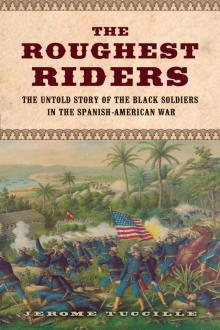

The Roughest Riders

The Roughest Riders Read online

$26.95 (CAN $31.95)

From The Roughest Riders:

“Buffalo Soldiers with Sumner’s Ninth and Pershing’s Tenth rushed ahead first, one of the men in the Tenth carrying his unit’s guidon as they ascended to within fifty yards of the peak. They were whooping and yelling, the taste of victory in their mouths as they closed in on the enemy entrenchments. ‘By God, there go our boys up the hill! Yes, up the hill!’ one of the troops yelled out, astonished. A moment earlier, it had appeared that they would all be cut down.

The cries of impending victory grew louder as they charged ahead, with most of Roosevelt’s remaining Rough Riders now beside the Buffalo Soldiers. Roosevelt was startled when a disoriented Spanish bugler, attempting to run away, ran into his arms instead and was taken prisoner. The yelling intensified when the first rank of Americans saw the Spaniards leaving their trenches and streaming southwest toward San Juan Hill, some returning fire as they ran, but most intent on avoiding the newly energized American army. The soldiers of the Tenth planted their guidon on the hill as the troops swarmed across the crest, with a clear view of the retreating defenders heading down the back slope in the direction of San Juan Hill. Roosevelt later claimed that the Rough Riders had planted their standard first, but one of his Rough Riders, Nova Johnson from New Mexico, said later, ‘You should have seen the amazement Colonel Teddy’s face took on when he reached the top of that first ridge, only to find that the colored troopers had beat us up there.’”

Copyright © 2015 by Jerome Tuccille

All rights reserved

First edition

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61373-046-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tuccille, Jerome.

The roughest riders : the untold story of the Black soldiers in the Spanish-American War / Jerome Tuccille. — First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61373-046-1 (cloth)

1. Spanish-American War, 1898—Participation, African American. 2. Spanish-American War, 1898—Campaigns. 3. African American soldiers—History—19th century. I. Title.

E725.5.N3T83 2015

973.8’9—dc23

2015001414

Interior design: PerfecType, Nashville, TN

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

To my grandsons, Jasper, Hugo, and Anthony

The powerful purpose of this monument is to motivate us. To motivate us to keep struggling until all Americans have an equal seat at our national table, until all Americans enjoy every opportunity to excel, every chance to achieve their dream.

—General Colin L. Powell, July 25, 1992, dedicating the Buffalo Soldier Monument at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas

Contents

Cast of Main Characters

Prologue

Part One: The Landing

Part Two: The Hills

Part Three: The Collapse

Part Four: The Aftermath

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Cast of Main Characters

Emilio Aguinaldo, also known as Aquino, the fiery leader of the revolutionary forces in the Philippines.

Joseph B. Batchelor, a captain who led contingents of Buffalo Soldiers and white troops in the Philippines.

Horace Bivins, a sergeant with the all-black Tenth Cavalry in charge of their Hotchkiss guns.

Charles Boyd, a captain reporting to Major Young in Mexico, where Boyd was killed in action.

Allyn Capron Sr., a captain and the father of the young Rough Rider killed at Las Guasimas.

Allyn Capron Jr., a captain with the Rough Riders who was killed in action in Cuba.

Venustiano Carranza, a former ally of Pancho Villa during efforts to overthrow the Mexican government, before the two men turned on each other.

Herschel V. Cashin, the only reporter covering the Buffalo Soldiers with Wheeler’s and Young’s forces in Cuba.

Pascual Cervera, vice admiral of the Spanish fleet stationed in Cuba.

Adna Chaffee, a general reporting to Lawton who came to the aid of the Rough Riders on several occasions.

Stephen Crane, the well-known author of The Red Badge of Courage and a reporter for the World who helped carry fellow reporter Edward Marshall to safety after he was shot.

Benjamin O. Davis, a black volunteer who would go on to become the first African American general in the US Army on October 25, 1940.

Richard Harding Davis, a noted reporter of the period who covered the war in Cuba for the New York Herald.

George Dewey, a naval commodore and commander of the US Asiatic Fleet dispatched by Roosevelt to the Philippines during Secretary Long’s absence from Washington, DC.

David Fagen, a Buffalo Soldier who became a legend after he switched sides and joined the rebels in the Philippines.

Hamilton Fish, the grandson of President Ulysses S. Grant’s secretary of state of the same name, and a Rough Rider volunteer killed in battle in Cuba.

Henry Flipper, the first black graduate of West Point.

Calixto García, the general in command of the Cuban rebel forces around Santiago de Cuba.

George A. Garretson, the general who commanded American forces, including Buffalo Soldiers, heading north from Guánica to Yauco in Puerto Rico.

Benjamin Grierson, the first commander of the Tenth Cavalry.

Edward Hatch, the first commander of the Ninth Cavalry.

Hamilton Hawkins, a general who came to the assistance of Lawton and some of his Buffalo Soldiers on San Juan Hill.

Jacob Kent, a general in command of the all-black Twenty-Fourth Infantry in Cuba.

C. D. Kirby, a first sergeant who wrote about the action he saw with the black Ninth Cavalry in Cuba.

Henry LaMotte, the aging surgeon and medical officer who served as a major attached to the Rough Riders.

Henry Lawton, a general in command of Buffalo Soldiers and white units in Cuba and, later, in the Philippines, where he was killed in action.

Arsenio Linares, the commanding general of the Spanish forces defending Santiago de Cuba.

John D. Long, secretary of the navy and Theodore Roosevelt’s boss at the time the USS Maine was sunk in Havana Harbor.

William Ludlow, a general who directed some of the key assaults on El Caney.

Edward Marshall, a correspondent for the New York Journal who was seriously wounded while covering the war in Cuba.

Edward J. McClernand, the lieutenant colonel who served as a top aide to General Shafter.

William McKinley, president of the United States during the Spanish-American War.

Enrique Méndez López, the lieutenant commanding a Puerto Rican militia unit in the coastal town of Guánica.

Evan Miles, a colonel engaged in much of the action around El Caney.

Nelson A. Miles, the commanding general of the US Army during the Spanish-American War.

Albert L. Mills, a captain who delivered Shafter’s message that Generals Wheeler and Young were being replaced in the field by Colonel Wood and General Samuel S. Sumner, the result of which was putting Roosevelt in sole command of the Rough Riders.

James A. Moss, a lieutenant who had experimented with the use of bicycles in warfare and fought with the Buffalo Soldiers at El Caney.

William Owen “Buckey” O’Neill, former mayor of Prescott, Arizona, and a captain with the Rough Riders who was killed in action in Cuba.

George S. Patton, the future World War II general who was a lieutenant reporting to Captain Pershing during the Villa exped

ition.

John “Black Jack” Pershing, the captain who led the Buffalo Soldiers of the Tenth Cavalry in Cuba before he became a legendary general during World War I.

Colin L. Powell, the general who was the first black chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and who later became secretary of state during the first Bush administration. Powell brought the Buffalo Soldiers into the national consciousness by dedicating the memorial in their honor at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1992.

Francisco Puig, the lieutenant colonel in command of the Cazador Patria Battalion in Yauco, Puerto Rico, who committed suicide when the Americans overran his defenses.

Robustiano Rivera, the lighthouse keeper in Guánica.

Theodore Roosevelt, the assistant secretary of the navy during the McKinley administration who later became the leader of the Rough Riders and president of the United States.

William T. Sampson, the naval captain who led the first inquiry into the sinking of the USS Maine and was afterward promoted to rear admiral in command of the United States’ North Atlantic Squadron.

William R. Shafter, the elderly commanding general of US forces in Cuba who had himself fought for the North during the Civil War.

Theophilus Gould Steward, the chaplain and only black officer with the Twenty-Fifth Infantry Regiment, the first troop ordered to war in Cuba.

José Toral, the Spanish general who replaced General Linares after the latter was wounded in battle.

Harry S. Truman, the president of the United States whose executive order integrated the US armed forces in 1948.

Joaquín Vara del Rey y Rubio, a Spanish general who was killed in action while defending the village of El Caney against the American assault.

Pancho Villa, the Mexican revolutionary who eluded attempts by the US government to capture him after he and his men raided a New Mexico border town.

Joseph “Fighting Joe” Wheeler, an aging Confederate veteran of the Civil War who served as a general in command of Buffalo Soldiers in Cuba.

Charles A. Wikoff, the colonel who led a unit of Buffalo Soldiers up San Juan Hill and there became the most senior-ranking American officer killed in action to that date.

Woodrow Wilson, president of the United States during World War I and openly hostile toward racial equality in the military.

Leonard Wood, a colonel and medical doctor, the head of the First Volunteer Cavalry, and the original leader of the Rough Riders.

Charles Young, the third African American graduate of West Point, who was also a captain during the war in the Philippines and a major during the search for Pancho Villa in Mexico.

Samuel B. M. Young, a general who was the second-in-command to General Wheeler.

Prologue

Lieutenant Colonel Theodore Roosevelt was worried about the condition of some of his men. They were cavalrymen, not foot soldiers, and this narrow path through rugged terrain required special stamina. Most of his Rough Riders were volunteers, cowboys used to making their way on horseback over flat western desert and prairie land, yet here they were, on hilly trails sometimes facing brush so thick they had to pass through it single file. Roosevelt, on horseback himself, led his men along the rugged wagon road following the coast. The day before, several hundred white and black soldiers had bushwhacked the trail under nearly impossible conditions.

Another column of soldiers, consisting of both all-white and all-black regiments, had blazed its own route through thick foliage a few hours before Roosevelt’s Rough Riders started out. The grueling path wound precipitously along the coast, causing some of the troops to stretch out like an accordion behind the men plowing on before them. One soldier later said, “They advanced as blind men would through the dense underbrush.” They continued their sluggish pace for five arduous miles toward Siboney, their first stop along the shoreline. The combined US forces that had landed so far totaled about a thousand.

Roosevelt urged his men to follow him as closely as possible as he rode ahead to catch up with the others in Siboney. The Cuban summer heat was unbearable, even as twilight approached; it had taken them all afternoon to navigate less than five miles under the worst conditions imaginable. The heavy loads the men carried on their backs made the temperature and humidity almost unendurable.

Roosevelt and his Rough Riders finally arrived the evening after the first column of soldiers had made camp. He ordered the men to rest as much as possible, in preparation for launching an assault on the well-fortified Spanish positions up in the hills. They bivouacked in a torrential downpour that lasted for hours near the dismal coastal village of Siboney, at the edge of the Caribbean just east of Santiago de Cuba. When the rain let up, the men fried pork and hardtack and washed it down with bitter coffee. Roosevelt had orders to set off at daybreak with the other regiments and make their way uphill toward Las Guasimas, a settlement located at the junction of two mountain passes. The Spanish had fifteen hundred or more regular army troops in place, with orders from General Arsenio Linares to hold off the Americans.

The Spanish soldiers had superior weaponry at their disposal. Most were armed with 7mm Mauser rifles with repeating bolt action, high-velocity cartridges, and smokeless powder. Supporting them from behind was an impressive array of artillery that could cut through trees and bring an avalanche of fallen timber down on the Americans’ heads. The Rough Riders and the other American troops carried more outdated equipment—smaller .30 caliber Krag-Jørgensen rifles and carbines, and Springfield rifles with carbon-powder charges that emitted black smoke and revealed the troops’ positions. Their artillery consisted of a four-gun detachment of older hand-cranked Gatling and Hotchkiss guns. Roosevelt moved forward and the American soldiers followed in his wake.

The Americans opened fire first, and the Spaniards responded with their rapid-fire rifles and artillery. The US guns filled the air with billowing dark smoke, while the Spanish weapons gave off no smoke of their own, making their emplacements hard to pinpoint. The Americans advanced blindly into the face of the whizzing bullets and cannonades raining down on them. Their noses filled with acrid smoke, their eyes burned like fire, and their ears rang with the deafening pounding.

Then tree limbs came crashing down and the American troops started to drop around Roosevelt, who continued his upward advance. Men were tumbling like bowling pins, some struck in the head, others in the groin and legs. Roosevelt was hit indirectly himself when a bullet smashed through a palm tree and showered him with splinters and wood dust. The sounds, smells, and taste of war smothered everything. The fighting raged for a couple of hours, and Roosevelt’s Rough Riders were struck especially hard, as they were in the lead now and were in danger of being completely cut down in their tracks.

Despite the chaos, US troops eventually prevailed against the Spanish defenses at Las Guasimas, the first battle in Cuba, thanks mostly to the intervention of black troops who prevented the Rough Riders from being wiped out. It would not be the last time black soldiers would come to the rescue. The Spaniards, meanwhile, pulled back and formed new perimeters a few miles farther uphill. One line of defense was at Kettle Hill, a second was strung along San Juan Hill, a bit to the south. Both positions would eventually be taken, but first came the major struggle in the miserable village of El Caney, a mountain town to the north.

A week after the Battle of Las Guasimas, the order came for the Americans to capture El Caney and the two major hills in the cradle of land known as the San Juan Heights. After a bloody day-long battle, American forces eventually overran El Caney thanks largely to the all-black Twenty-Fifth Infantry Regiment. Roosevelt was assigned to focus the Rough Riders on Kettle Hill, situated between San Juan and El Caney. There, Roosevelt’s troops came under heavy fire from the Spaniards, who were laid out along the crest, ensconced in hand-dug trenches that kept them shielded from—yet gave them a somewhat truncated view of—approaching hostile forces. Other Spanish troops were well hidden behind stone barricades and inside blockhouses that provided good protection against the adva

ncing Americans.

Roosevelt attempted to put his Rough Riders in the lead, but he and his men had trouble keeping up with the regulars of the all-black Tenth Cavalry, under the command of Captain John “Black Jack” Pershing. Together, they pushed on through blistering enemy fire, taking heavy losses as they slogged uphill. In general, the Spaniards occupied well-concealed positions, although they were not entrenched in what the Americans would have considered the most advantageous locations. Had it been them defending the hill, they would have placed most of their troops along a lower promontory on Kettle Hill—the “military crest”—a hundred yards or so below the geographical peak. That would have given the defenders a more commanding view of the downward slope, providing them a clear, unobstructed line of fire. Still, there was little question that the enemy had the advantage, lying in trenches as the Americans climbed under great duress.

The Spanish continued to unleash all their firepower, inflicting mounting losses on the Americans. Near the brink of disaster, the attackers managed to maintain their forward momentum and suddenly became invigorated by the sight of the Spanish flag on the crest. The all-black regiments, including Pershing’s Tenth and the black Ninth to their left, charged past the Rough Riders toward the clearing near the top, lacing the air with chilling battle cries they had learned in earlier wars. They ran ahead furiously and courageously, seemingly without regard for their own lives and safety. The specter they created took the Spaniards by surprise and shocked them with the sheer ferocity of the attack. The Spanish gave way, some throwing down their weapons while others broke and ran down the paths leading southward toward San Juan Hill.

Roosevelt’s Rough Riders followed the black soldiers to the peak as the Spaniards streamed down the far side of the hill. But Roosevelt had been delayed a moment earlier when his horse became ensnared in a barbed wire barricade, halting his progress and forcing him to climb the rest of the way on foot with his remaining men struggling up behind him. Once there, the Americans stormed together over the abandoned Spanish fortifications, unable to believe that they had prevailed in the face of what looked like certain annihilation just minutes before. Kettle Hill was theirs now, totally vacated by enemy troops except for the dead and wounded.

The Roughest Riders

The Roughest Riders Hemingway and Gellhorn

Hemingway and Gellhorn